The Review/ Feature/

Interview/The Highs and Lows of Writing and Directing Your Own Work

This year's TIFF Studio participants curate The Review and share their feelings on writing, directing, and how to fix the Canadian film industry

__For the Canada Day edition of the Review newsletter, we asked the current residents of TIFF’s year-round Studio program, which focuses this year on writer/directors, for thoughts on their creative process and the local film industry. Here are their responses, edited for length and clarity. Your curators are (in alphabetical order): Adam Garnet-Jones, Ashley McKenzie, Eisha Marjara, Igor Drljaca, Joyce Wong, Kevan Funk, Linsey Stewart, Mark Slutsky, Maxwell McCabe-Lokos, Molly McGlynn, Simon Ennis, and Tracey Deer. Interview by Chandler Levack. __

Adam Garnet-Jones' Fire Song

When did you realize that you wanted to make movies? Describe what this means for your career as you enter TIFF Studio.

Adam Garnet-Jones: When I screened my first film at age 14, I felt for the first time like I was being deeply seen and heard, while hiding behind the camera where it was comfortable. Entering TIFF Studio feels like a massive gift. I'm at a point where I could go in a lot of different directions with my work, so I'm trying to muster the strength and bravery to aim higher and paint with brighter colours.

Ashley McKenzie: I got bored with drinking in the woods and ditches of my small town as a 13-year-old, so I abandoned my friends and started renting old movies. Schooling myself in cinema stuck, and I started writing “film director” as my preferred future occupation. A few years later, I saw Parsley Days on TV in the middle of the night and found out that it was directed by a young woman in Nova Scotia named Andrea Dorfman. Having her as a model is when I realized making movies was a tangible thing I could do.

Eisha Marjara: I always knew I was an artist. Being a director came to me while I studied photography at Dawson College. My love of photography and directing plays in high school fused and became my love of cinema. I just completed my feature film Venus and feel like I am exactly where I want to be.

Igor Drljaca: The day I realized my accent would make it difficult to be an actor. In all seriousness, I realized it in Grade 10 after making a few video projects. I am just really grateful that I am still doing something I love.

Joyce Wong: It was a gradual process inspired by the scarcity of films that reflected my perspective and experiences as an Asian woman. I think it’s important to be able to identify with characters and stories you consume in mass media because subconsciously, if I can see that other people are feeling the way I am thinking/feeling, it means I’m not alone. I like being in creative environments with people who inspire me; I think TIFF Studio will be like that.

Linsey Stewart: Ever since I was a kid, I would tell my mom that I felt like a trapped artist. I had something to give, I just didn’t know how to express it. For a while, I thought that thing was copywriting, but there’s only so much Mr. Clean copy a gal can write before she questions every decision in life she’s ever made. During a late-night binge of Six Feet Under, it hit me: I want to tell stories. I’m absolutely jazzed to be a part of TIFF Studio. I have to be doing something right if I get to be included in this talented group of filmmakers.

Mark Slutsky: I was terrified the day I first ran my own set for real. In the days and weeks leading up to it, I basically lost my mind and alienated everyone around me as I stewed in my anxieties. The moment we actually started shooting, it was such an exhilarating, giddy feeling, I knew I’d never want to do anything else ever again.

Mohawk Girls by Tracey Deer

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos: There was no exact moment I realized this. It was an accumulation over the years until it's too late to back out, so you might as well commit. I recognize I am only a beginner, but TIFF has been a big part of why I chose to get into filmmaking. Being part of TIFF Studio helps me to choke that ever-present voice in my head telling me I'm an imposter.

Molly McGlynn: I think I could be a good teacher or a social worker, but I want to do this. I am in a privileged position where I’m supported in my desires and drive towards a creative life. A moment of realization came on the last day of shooting my forthcoming feature — the AD called “wrap” and I burst into tears because I fucking did the thing I never thought I would get to do! TIFF Studio is coming at such an exciting time when my identity as an artist is becoming less amorphous, something I can see concretely in front of me.

Simon Ennis: I was nine and addicted to movies, but I wanted to be a detective. My dad, Paul, and his friend Bob (both cinephiles and former owners of the Revue Cinema) were at my house, taping a show on TV. A few weeks later, Bob said, “Simon, if you want to be a detective and you love mysteries, maybe you’d like this show we’ve been taping.” He popped a tape in the VHS player, we watched the first three episodes of Twin Peaks, and it totally lit my (admittedly already very weird) nine-year-old brain on fire. It was so different, compelling, and hypnotic; I was instantly obsessed. Beforehand, I had been totally focused on the actors in movies, but this show had such a unique world that I became conscious of its construction. I was told that the person who made it that was David Lynch, the director.

Tracey Deer: I was 12 years old, watching movies on a VCR my father would rent every weekend from the local video store on our reserve. Every film took me on an incredible journey; by the end, the main character had inspired me to declare a new future career. After four months, it dawned on me that if I made movies, I would get to experience every single one of those stories. I received the message over and over again that my dreams were impossible because of the very low expectations this society has of Aboriginal people. With my mother’s constant encouragement and my people's resiliency to inspire me, I’ve set out to prove we are just as capable as everyone else.

Ashley McKenzie's Werewolf

There’s been a lot of press lately about “the next generation of Canadian filmmakers.” Do you feel like we’re in a uniquely fruitful time for Canadian film?

Adam Garnet-Jones: My community is mostly Indigenous filmmakers, some of whom are Canadian. It's an exciting moment for Indigenous filmmakers, although the gates seem to be opening just as budgets shrink and the industry as a whole is in freefall. It sometimes feels like opportunities for women, Indigenous filmmakers, and people of colour are coming because the recipe for success crafted by the largely straight, white male industry has stopped working.

Ashley McKenzie: I’ve had the privilege of travelling across Canada for the past 10 months with my first feature, allowing me to connect with a whole new wave of filmmakers and critics. I think this year will be a particularly fruitful one for Nova Scotian cinema, as there are four features coming out from distinct and daring voices: Mass for Shut-Ins by Winston DeGiobbi, In the Waves by Jacquelyn Mills, The Crescent by Seth Smith, and Black Cop by Cory Bowles.

Linsey Stewart: I’ve made almost everything here, tapping into our revered funding systems, but I’ve had almost all my success in the States. I love the Canadian film community, but it can feel a little limiting and frustrating. When an industry executive sees a Canadian film and digs it, rarely do they reach out and say, “Hey, interesting filmmaker, I like your movie and want to find a project that we can work on."

Kevan Funk: I feel connected to this idea of a younger generation of filmmakers looking to push forward a different — hopefully more bold and self-assured — idea of what Canadian cinema should be. It's heartening to acknowledge that my peers are the ones I’m most inspired by.

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos: I don’t identify as a Canadian filmmaker. I love to work with many wonderful people in Canada, but I do not see my ideas as representative of anybody but myself. The word "community" makes me feel nauseous, which is strange because I consider myself a devout socialist.

You Might As Well Live, from writer/director Simon Ennis

Mark Slutsky: I live in Montreal but don’t feel super-connected to the film community (which I dig and respect a great deal, don’t get me wrong!). I think there is a tremendous amount of cool and inspiring work being produced by young Canadian filmmakers right now, particularly ones who are deft at creating films that inhabit their budgets and circumstances of creation.

Molly McGlynn: I grew up in the United States but, ultimately, my professional development and support has mainly come from here. It feels like an exciting time because filmmakers are finding a way to make work, regardless of whether they have traditional funding streams. “Canada the Nice” is starting to get a little bit of a “Fuck It” attitude.

Simon Ennis: I’m personally uncomfortable identifying as much of anything… except maybe as a cat lover. As far as community? Well, I did train my friend Kazik Radwanski at the video store we worked at; a few weeks back my buddy Hugh Gibson subbed in on my softball team; Nadia Litz and I walked dogs together the other day, and Max McCabe-Lokos was at my house listening to early ’90s dancehall records until 4am. As far as it being a uniquely fruitful time for Canadian film, there are some really great movies being made, as well as a bunch of lousy ones. Isn’t that always the way?

Kevan Funk's Hello Destroyer

It can be difficult for Canadians to see Canadian films due to a lack of marketing and distribution. What do you think we “owe” Canadian audiences in the films we’re making?

Adam Garnet-Jones: I think we owe it to Canadians to challenge them. I wish we made more “bad” movies because filmmakers were encouraged to have the boldest possible vision. It’s particularly true of Indigenous, Queer, and racialized artists because our stories are already seen as a gamble.

Eisha Marjara: If there’s anything Canadian filmmakers “owe,” it’s to stop looking over our shoulder at what other people are doing.

Joyce Wong: It’s not necessary to have a political agenda, but our films should have a point and come from a genuine intent to tell stories.

Kevan Funk: Having just released a film theatrically across Canada, this is a very broad issue with no simple fix. One of my biggest frustrations is the way parties on all sides (filmmakers, festivals, distributors, broadcasters, funding bodies) tend to be extremely reductive in the way they talk about this. Instead of acknowledging complex issues that need to be solved, everyone looks to find one simple solution, which doesn’t exist. I personally feel like all of us owe it to Canadians and ourselves to make bolder, braver work.

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos: The idea that a filmmaker "owes" something to anyone sounds crazy to me, not to mention extremely limiting and downright submissive. If I'm a Canadian citizen, my opinions and my films are Canadian by proxy, regardless of what they’re about, or where they’re shot.

Molly McGlynn: There’s a lot of talk about the Canadian funding mechanisms and frankly, it’s not perfect. But I know Americans who would kill to have a publicly supported industry. The most important and obvious thing is to go see your friends’ movies. Retweet or post about Canadian filmmakers. Be generous. I don’t think we “owe” Canadians anything, except being true and specific about we’re trying to say.

Tracey Deer: I think we owe the audience a good ride. We owe them solid story structure, clear themes, and three-dimensional characters they can fall in love with. As storytellers, we are very privileged to be in this position, so we have a responsibility to deliver our very best.

“I don't think screenwriting is therapeutic. It's actually really, really hard for me. It's not an enjoyable process.” — Charlie Kaufman

A clip from Eisha Marjara's Desperately Seeking Helen

__What kinds of films turn you off? __

Ashley McKenzie: The last few times I walked out of movies was due to excessive male gaze vibes felt in the filmmaking and in the construction of female characters.

Eisha Marjara: I am tired of blockbuster superhero franchise films. They’re indulgent — an entertainment shopping mall.

Igor Drljaca: Many tentpole films. The main issue is not scale, as some can work well (Mad Max: Fury Road, Arrival); rather, it’s uninspired “by-committee” filmmaking that takes no risks.

Kevan Funk: The thing I find the most bothersome is when you’re simply going through the tired-but-true motions of three-act structure. Those films can be technically well-made, well-acted, and well-written, but it's an incredibly dull experience. I want to see work that’s actively trying to engage me and offers a sense of agency. I don't want a passive experience.

Linsey Stewart: Films that are low-brow, half-baked, meandering, or have characters who are actually abusing each other (but think they’re being really charming).

Mark Slutsky: My biggest turn-off is total self-seriousness. Almost everything I like has some sense of humour about itself, even the most serious work.

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos: Sentimental movies; movies that want to teach me a lesson; cloying movies; movies that totally rely on current cultural references; jingoist movies; boring, self-indulgent art movies. I think blunt stupidity gets in the way of good storytelling, and so does over-indulgence.

Molly McGlynn: I recently sat through Paul Blart: Mall Cop 2 because I deeply adore my nephews, but I wanted to gouge my eyeballs out. Why is this dude making his smart and capable daughter (who I first thought was his wife) feel bad about “abandoning” him by going to college?

Simon Ennis: Talking down to the audience. There’s a moment in Steven Spielberg’s Munich where the signal for one character to assassinate another is a light turning on in a hotel room. The device is established, it’s an honest-to-goodness neat trick to create tension, but Spielberg can’t help but cut to two characters in a car, as one talk-whispers the equivalent of “Remember, the signal to assassinate ‘Character X’ is the light going on.”

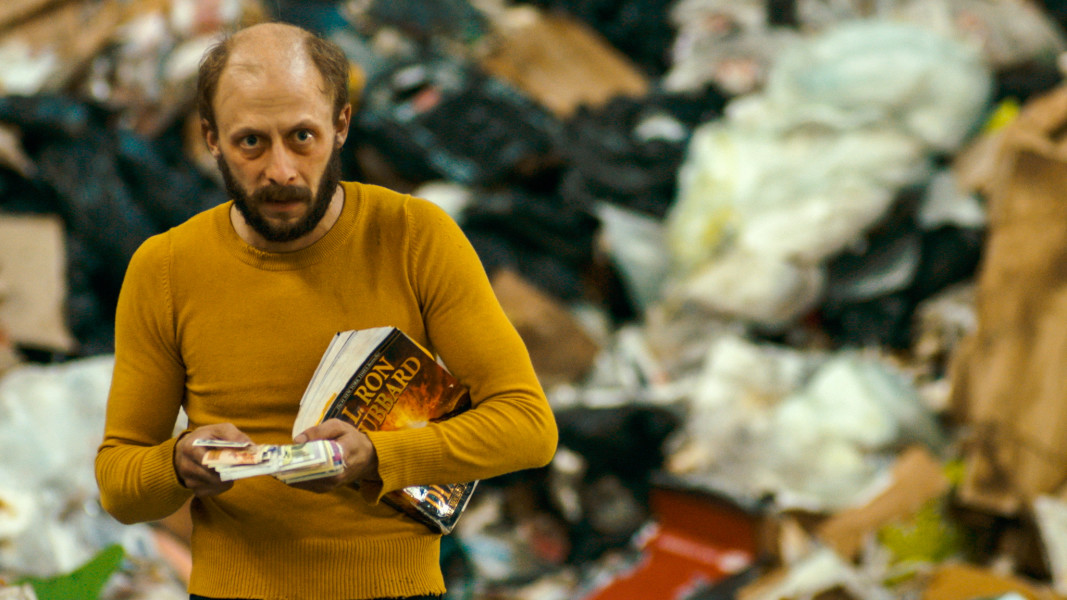

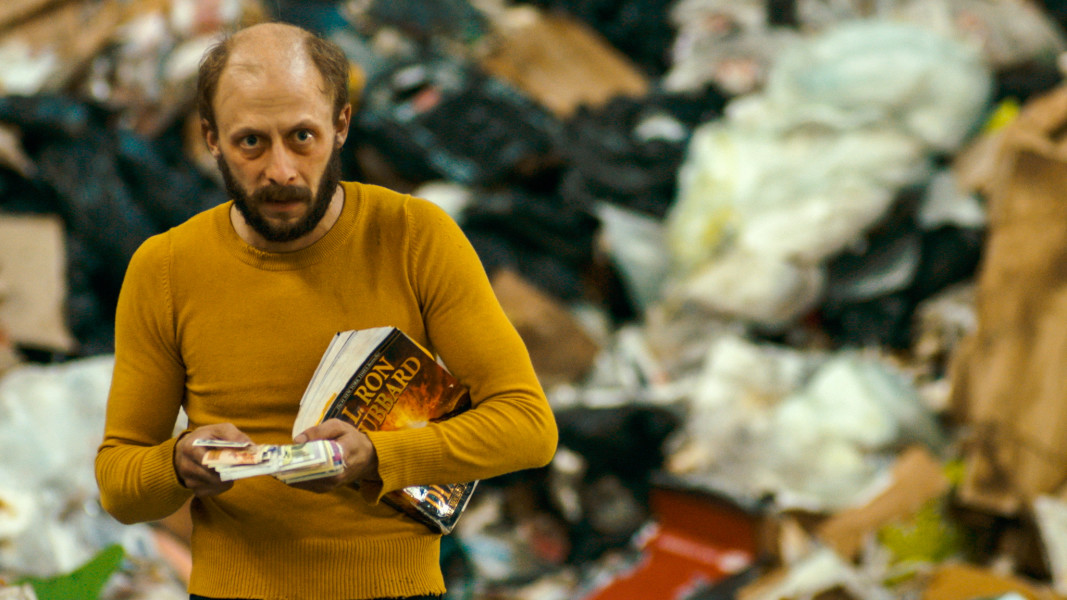

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos' Ape Sodom

If you had the power to change the Canadian film industry, what immediate actions would you take?

Adam Garnet-Jones: I’d place the highest level of importance on artistic and cultural value. I would want the industry to support only the boldest visions, the stories that have the most to say about who we are. I would market these films as an essential part of the cultural conversation because they would be.

Igor Drljaca: Canadian filmmakers lack the resources to distribute and market films and are dependent on outdated distributor models. Bigger Canadian distributors have distanced themselves from Canadian films, as fewer and fewer titles are picked up. Unless there is a mandate, there will be fewer films being distributed through traditional theatrical means. It’s a quantity dilemma as more work is being made, but also a structural problem that doesn’t address the changing nature of our industry.

For Canadian films to be commercially viable, they need an almost equal amount of resources to market them as to produce them. When one applies an American studio formula to Canadian film shot on a reduced budget with public funding, not only is it a waste of money (as the films never make a return on investment), but it also restricts filmmakers creatively. If we want Canadian film to be more visible, we need stronger mandates to protect it. It’s less a problem with the quality of the films, but more with the lack of funding to properly promote their work.

Linsey Stewart: Just like any studio, there has to be accountability. I hate to use this dirty word, but this is a business. It often feels like there’s a pool of money and we distribute it to the same filmmakers, even if their last film was a dud.

Mark Slutsky: Make it way more diverse and less geographically confined.

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos: First, I would get rid of the cretinous idea that a short film is a proof-of-concept for a TV series. Then I’d replace anybody who chimes in on financing or grants funding who works for a corporation with someone completely objective and familiar with art, literature, and film from around the world. One thing that would improve the industry is if everyone stopped worrying whether movies represent Canadians and just made movies.

Molly McGlynn: I think the most concerning thing is a homogeneity of voice, which is a shame because we are such a diverse country. I would make a publicly financed fund that targets underrepresented voices in film (starting from high school) and pair them with established mentors to make films. Also, I really wish we worried less about creating a “star system” and worried more about developing talents who will reach the international stage by sharing their view of the world. Did I watch Moonlight for any specific talent? While I’m at it, we tend to idolize Canadians who have gotten recognized in Hollywood. That’s great, but does it mean we have to leave every single door of opportunity open to that person forever?

Simon Ennis: I literally just came up with this idea off the top of my head. First, put an immediate five-year moratorium on Telefilm funding films by directors over 40 who have made three or more feature films. Using all the bread saved there, green-light two feature films each from a very wide and diverse selection of directors (under 40 with under three features in the can) at a combined budget of two to three million dollars, which can be split between the two projects at each filmmakers’ discretion. Choose the filmmakers by a lottery system, which accounts for and assures diversity, and give the filmmakers final cut. This would be a massive shakeup allowing emerging filmmakers to experiment and make mistakes (that’s why everybody gets to make two). At the end of five years, lift the sanctions against the “old masters.” The new lay of the land will dictate what projects get funded going forward.

Tracey Deer: The ability to finance large-scale productions would be a big help.

Molly McGlynn's short film 3-Way (Not Calling)

If you happen to identify as a writer/director, what are the challenges (and joys!) of directing your own work?

Adam Garnet-Jones: The biggest challenge is not living up to my own expectations. That shit can be crushing some days.

Igor Drljaca: My joy comes from working on a scene that was written one way, and through the collaborative nature of working with actors and key crew members it becomes something even more unique. My frustration lies in the financing and distribution stages of the project.

Joyce Wong: I am very self-critical when I am directing my own writing, so sometimes I have the urge to throw out the baby with the bathwater.

Mark Slutsky's Never Happened

Linsey Stewart: I hate everything I do, but I love the challenge of trying to grow as a filmmaker. Every scene I write is my problem, I’m the director for hire, so I better know what the hell I want out of it.

Mark Slutsky: The main joy of directing my own work is getting to actually do what I love — collaborating with actual human beings and not staring at my computer — for a few days a year. The challenge is to forget you wrote the thing and be able to explore the script from another perspective, lest you get too hermetically locked into your original vision.

Molly McGlynn: I laughed out loud thinking of the 10,000-word essay I could write on this subject. I’m challenged by crippling anxiety that my work is not good enough, or I am not good enough, but therapy and just doing the thing helps. What keeps me going? That feeling in your bones you get for 10 seconds when every element you’re in charge of aligns and you know you’ve nailed it.

Simon Ennis: As a cat lover who happens to write and direct films: the greatest joy is that you have one less person to argue with and the greatest challenge is that you have one less person to collaborate with.

Tracey Deer: It’s all a joy, even the challenges! I’ve wanted to do this ever since I was 12 years old — directing my own work is nirvana.

The short film Long Branch, co-written and co-directed by Dane Clark and Linsey Stewart

Are you a writer/director by choice? What skills are necessary to develop for both practices?

Adam Garnet-Jones: You have to choose to be a writer/director every single day. No one is going to bust down your door, and lots of people are going to tell you in a million little ways to stop. Writers have to go deep inside themselves, they have to sit and wrestle with uncomfortable questions, and they have to be disciplined about sitting all alone and doing the work, even though no one is asking for it. Directors have to have faith in their instincts, and be able to not only think but also act on their feet. There is no time for deep reflection on set. They also have to be a cheerleader, acknowledging everyone's artistry, and reminding them why they’re there in the first place.

Ashley McKenzie: I’m a filmmaker by compulsion. I write in order to direct, but want to train myself to be a better writer. I enjoy research, scouting, and casting, most of all; I love taking in the sounds and textures of spaces, getting to know new people, seeing inside their houses, their basements, their closets, getting inside their head. I quickly start to see films form and play out in detail in my mind. Harnessing all of this fascinating stuff into a structured narrative in front of my computer screen is like pulling my teeth out and scratching my face off.

Eisha Marjara: I’ve written all the films I’ve directed and it didn’t occur to me to have it any other way. Witnessing one's words translated onto the screen is undeniably exhilarating and deeply fulfilling, not to mention humbling. As the writer, I have a responsibility to the story, the characters, and to speak as truthfully as I can.

Igor Drljaca: In the process of writing, I often think I know how the scene will work best, but this is rarely true. Knowing when to let go is a difficulty writer/directors have.

Joyce Wong: I enjoy the writing process more than directing because there’s more creative freedom. You are alone with your characters, they dance around your head in situations you imagine for them. The directing process brings in many logistical restrictions where you’re responsible for balancing all sorts of creative collaborations to make it work.

Linsey Stewart: I love physically making the film more than sitting down for six years to write it. So many times I feel like I’m not making progress but when I’m on set, it’s all happening. The skill writers need to learn is how to tell a solid narrative. Every great film has great structure and pace, they just use their voice to make it special.

The Waiting Room by Igor Drljaca

Mark Slutsky: I think that since I can write, it would be wasteful not to, because of the control and ownership I can have over the idea from start to finish. As for the most joyful part of the process, it is 100 per cent getting to work with other actual human beings and profit from their talent and ideas. I’m a real extrovert — being around people energizes me more than almost anything else — so it’s pretty dumb that I’m a writer.

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos: I like both aspects equally, though I usually write with a co-writer. There's nothing wrong with directors who don't write if it doesn't suit them. Too many directors feel pressure to write and direct when it’s painfully clear they’re not good at both.

Molly McGlynn: It took me years to gain the confidence and delusion to pursue this as a real thing one can do with their life. I was quiet in film school and scared of failing in production classes. It took me a long time to understand that the performance of confidence is what impresses people into thinking you are capable. I ultimately got drunk on the realization I could write make believe on paper and have good looking people act it out.

Simon Ennis: My favourite parts of filmmaking come near the end. My friend Matt Lyon (who has edited all my films) has told me on several occasions that I write and direct movies, just to get to edit them. I love being in that little box, chiseling away, getting everything just so. The limitless opportunity of that undo button is both freeing and comforting! The biggest joy is the mix because pretty much all the decisions have already been made and that big soundboard opens up the world you’ve created and fills it in with magic. Perhaps the Dorothy Parker quote “I hate writing, I love having written” applies to me!

Tracey Deer: I like being in control from start to finish. Since I get to do that as a writer/director, I am definitely one by choice. The most joyful part is when I stop writing! It doesn’t matter whether it’s brilliant or rubbish, because there will be many more drafts, but I celebrate every time I take another step in the process.

Wexford Plaza by Joyce Wong

The TIFF Studio participants, in their own words:

Adam Garnet-Jones wants to tell stories about deeply flawed people in transformative times, especially within his Queer and Indigenous communities. His debut feature, Fire Song, played the Toronto International Film Festival in 2015, and his second feature, Great Great Great won Best Film, Best Screenplay, and Best Performance at the 2017 Canadian Film Festival.

Ashley McKenzie lives in Cape Breton. Her first feature, Werewolf, screened at the TIFF ’16 and at the Berlinale. She’s captivated by ordinary people and the fine and gritty details therein.

Eisha Marjara addresses universal themes in her films with emotion, humour, and sensuality. Her NFB feature docudrama Desperately Seeking Helen won the Critic’s Choice Award at the 2000 Locarno Film Festival. Her new feature, Venus, is about a transgender woman who discovers she has a son.

Igor Drljaca was born in Sarajevo, moved to Canada in 1993, and completed his MFA in Film Production at York University in 2011. He is the writer/director behind the features Krivina and The Waiting Room, both of which screened at TIFF.

Joyce Wong blends her comedy with humanity and is interested in exploring stories about outsiders. Her first feature, Wexford Plaza, premiered at Slamdance this year.

Kevan Funk makes work that engages with cultural criticism, cultural reflection, and personal narrative. His debut feature, Hello Destroyer, premiered at TIFF ’16 and was selected for the Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival.

Linsey Stewart likes to put humour, heart, and pain into her films. They include the feature I Put a Hit On You, which premiered at Slamdance in 2014, and the Vimeo Staff Pick Long Branch, co-directed with her filmmaking and life partner Dane Clark.

Mark Slutsky gets inspiration for sci-fi film ideas from napping. His previous work includes the short films Sorry, Rabbi, The Decelerators, and Never Happened, which premiered at TIFF ’15 and played the Tribeca Film Festival.

Maxwell McCabe-Lokos describes himself as a satirist who wants to explore topics like unbridled capitalism and the narcissism of small differences. He co-wrote and starred in Bruce McDonald’s film The Husband, which played TIFF in 2013, and premiered his short film Ape Sodom at TIFF ’16.

Molly McGlynn premiered her latest short film 3-Way (Not Calling) at TIFF ’16, and she has just finished production on her first feature, Mary Goes Round. Molly is interested in making films in which her (mostly female) characters try and fail at learning how to be human beings.

Simon Ennis likes to make movies about people on the fringe of society. His dark comedy You Might as Well Live, and his comic doc Lunarcy! have played festivals worldwide, including TIFF, SXSW, Telluride, and Fantasia.

Tracey Deer is the writer, director, and showrunner of the TV series Mohawk Girls, now in its fifth season. She is co-wriiting her first feature with Meredith Vuchnich and seeks to tell stories that entertain, enlighten, and build bridges.

React to The Review

We believe a powerful film or work of art — or, uh, email newsletter — should generate a reaction. That's why we're thrilled when readers of this humble publication choose to reach out and tell us what they thought. If you've got something to say, please SEND US A LETTER.