The Review/ Feature/

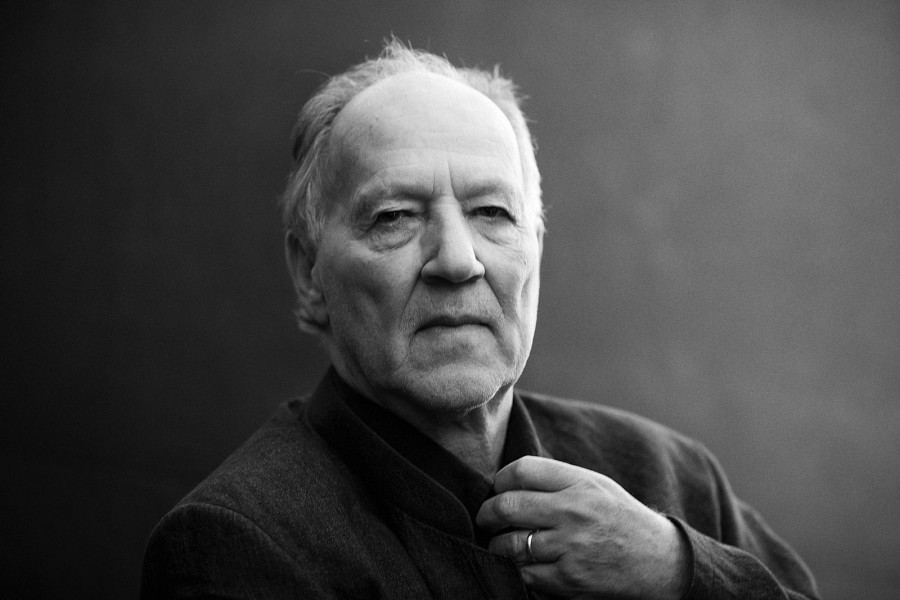

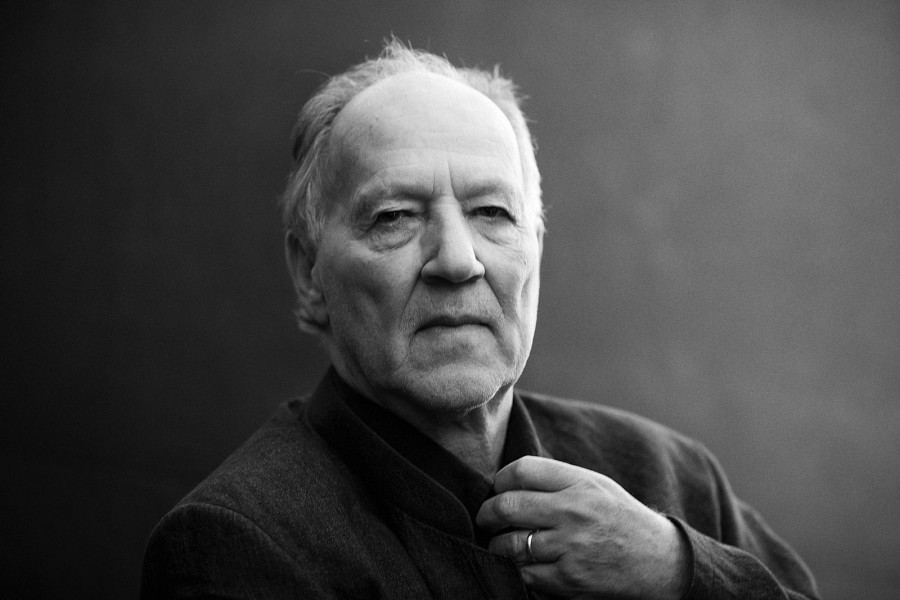

Werner Herzog, Cinema’s Most Curious Filmmaker

Whether investigating Pokémon Go or volcanoes, his iconic vision goes the distance

Werner Herzog has never stopped being curious. In the last decade alone, he has made a Vietnam P.O.W. drama, a New Orleans-set crime procedural, a biopic of Gertrude Bell, documentaries about the internet, the Antarctic, death row inmates, and the world’s oldest cave paintings, plus arguably the most acclaimed driver’s ed safety film of all time. Now, at age 74, Herzog has two new films at TIFF 16. They are Into the Inferno, a documentary about volcanoes playing Sept. 13 at Scotiabank and Salt and Fire, an ecological thriller playing Sept. 15 at the Elgin with Michael Shannon and Gael García Bernal. While no one knows how they’ll yet rank in the exhaustive Herzog canon, the man has never made an entirely dismissable film. If Werner Herzog finds something interesting, it probably is.

How many filmmakers have given us so many unforgettable images? You can rattle off a half-dozen iconic ones without even thinking. The conquistadors’ descent from the mountain in Aguirre. The steamship on the hill in Fitzcarraldo. The topless army in Cobra Verde. The little-person revolution in Even Dwarfs Started Small. The dancing chicken in Stroszek. The burning oil fields in Lessons of Darkness.

Those are show-stopping moments, but almost every Herzog film finds the poetry hidden in plain sight. In La Soufrière, he lingers on a traffic light that keeps blinking after the town has evacuated. In Wild Blue Yonder, he recontextualizes Antarctic underwater footage and space-shuttle documentary video into a sci-fi story, making familiar images seem otherworldly. In Grizzly Man, he finds “glorious improvised moments” in Timothy Treadwell’s reams of nature footage. And two years after March of the Penguins, his Encounters at the End of the World showed a lone, mad penguin breaking off from the annual breeding ritual to run—just run—into the distance, to its eventual demise.

He has spoken of the “voodoo of location” and his films are overwhelming sensory experiences. The jungles of Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Fitzcarraldo and Rescue Dawn pulse with the “fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for surviving and growing and just rotting away” that Herzog speaks of in Burden of Dreams. There’s the American midwest of Stroszek — grey, bleak, but with a certain cold, austere beauty. The post-Katrina New Orleans of Bad Lieutenant, seamy and dilapidated. Herzog is the only commercial filmmaker to have filmed on every continent, and none of them look like they do in any other film.

For someone who views the human race with a skeptical eye, he is still powerfully humanistic. He has (clear-eyed) affection for hopeless dreamers like Timothy Treadwell and Brian Sweeney “Fitzcarraldo” Fitzgerald, and loves incurable eccentrics like Bruno Stroszek. In Land of Silence and Darkness, he observes a lifelong deaf-mute and finds that even those unable to comprehend their own existence still respond to a human’s touch. In Lo and Behold: Reveries of a Connected World, he marvels that humans have been able to create something as extraordinary as the internet, and is empathetic towards a species that is completely unequipped to deal with this responsibility.

Though lumped with Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Wim Wenders as part of the 1970s “New German Cinema,” Herzog can’t be pinned down to any particular movement. He has cited F.W. Murnau, Tod Browning, D.W. Griffith and Akira Kurosawa as favourite filmmakers, but aside from Murnau (whose Nosferatu he remade), I think he sees them more as fellow travellers than direct influences. The pacing, camerawork, acting style and atmosphere of his films are so singular that it’s not a surprise to learn he grew up mostly ignorant about film history.

Herzog’s oft-repeated origin story (which by now has now reached the status of Creation Myth) is that he moved with his family as a small child from Munich to a small Bavarian village to avoid the bombings of World War II. He claims to have been unaware of the existence of movies until age 11, and to have made his first phone call at age 17. He became compelled by filmmaking in his late teens (famously stealing a camera from the Munich Film School), but says that he sees only a handful of films a year. His own Rogue Film School teaches such practical skills as picking locks and forging shooting permits, instead of film history or theory. Unlike a lot of filmmakers, he doesn’t give the impression of having learned about life through watching movies.

Speaking from personal experience, I know that Herzog is a gateway to cinephilia, and that he is one of the most accessible of the world cinema titans. A lot of this has to do with the basic potency of his images and characters. Another part of his appeal is that he has turned himself into a Captain Ahab-like literary hero. His fans relish the wild stories about his life: that he walked from Paris to Munich when he learned his friend, the critic Lotte Eisner, had fallen ill; that he threatened to kill Kinski; that he ate his shoe on a bet; and that he ordered a goddamn ship to be pulled over a mountain, despite everyone telling him he was crazy. The production of Fitzcarraldo led many to call him an irresponsible megalomaniac, and since then has skillfully managed his legend. The idea that My Best Fiend (about his relationship with Klaus Kinski) communicates most loudly is, “Hey, don’t get the wrong idea. He was the crazy one.”

In 2005, Herzog’s blasé reaction to being shot (“It was not a significant bullet”) helped turn him into a Chuck Norris-like internet meme. So many interviewers have asked Herzog to comment on pop-culture ephemera that it has practically become a clickbait genre — film culture’s version of that poster of Einstein sticking his tongue out. Calum Marsh wrote scornfully of “the memeification of Werner Herzog” in the National Post: “It’s a fairly abhorrent way of treating one of our major living filmmakers. Werner Herzog isn’t Christopher Walken. He ought to be valued for his genius, not regarded as a joke.” Yet, concentrating solely on Herzog’s art is a challenge, because he has made his personality and his off-screen exploits so crucial to his legend.

A downside to Herzog’s “memeification” is that it seems to have encouraged his occasional swerves toward self-parody. The ending of Cave of Forgotten Dreams with that non sequitur coda about albino alligators, and the “Does the internet dream of itself?” digression in Lo and Behold felt too much like contrived Herzog Moments™. Even so, he is still capable of creating a documentary as sober and shtick-free as Into the Abyss, his In Cold Blood-like study of a massacre in Texas. And if contriving Herzog Moments™ means we sometimes get the “dancing soul” from Bad Lieutenant, or the rant against “abominations such as an aerobic studio and yoga classes” in Encounters at the End of the World, the history of cinema is better for it.