The Review/ Feature/

Deepa Mehta Shares Her Journey in Film (Death Threats Included)

The acclaimed filmmaker details why women must make films and live life on their own terms

I don't remember picking up a camera when I was a kid, but I like the idea of imagining my younger self full of innovation and style, utilizing a variety of cinematographic equipment. Alas, my earliest exposure to films was in front of the screen. I was a reader and thought cinema gave another dimension to the written word.

My father was a film distributor and theatre owner in Amritsar, a city in northwestern India. After school, my brother (filmmaker Dilip Mehta) and I would watch movies while waiting for Dad to finish work. The first film that changed my life was Wadlal Jaswantlal’s Nagin. I remember being mesmerized by Vyjayanthimala’s attempt to outdo a cobra in the dancing department, while swaying to a snake charmer’s flute. Dad took us upstairs to the projection room, and we learned from Ram Lal, the projectionist, how reels for 35mm film were threaded, loaded, and changed. We then climbed the four steps that took us to the stage. As I touched the fabric the screen was made of, Dad signalled the projectionist. On cue, we were bathed in the distorted black-and-white image of Pradip Kumar and his weird lipsticked mouth — pure magic.

I don't remember ever watching a film with an audience as a kid. Ensconced in my private viewing room, I felt free to express the extreme emotions evoked by a movie: copious tears, unrestrained laughter, and wild, appreciative applause. Years later, when I watched Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso, I felt the instant recognition of falling in love with a medium before recognizing that cameras were involved. My love affair with filmmaking would start much later.

Cinema Paradiso, 1988.

One of my first heroes growing up was Mr. Rick. He was the only person I truly liked at my rather dry, old-fashioned, all-girls boarding school in the foothills of the Himalayas. Every Sunday at four in the afternoon, come rain or shine, Mr. Rick would ride his bike through the imposing wrought-iron gates of my school. Secured with rope to the back of his bicycle carrier was a dodgy 16mm projector, and slung across each shoulder in a cotton sack were aluminum reels of the “surprise” movie designed to mind a gaggle of 13-year-old girls starved for entertainment and the allure of Hollywood. Miss Linnell, our formidable British headmistress, thought the song-and-dance and melodrama of Indian Cinema would make the students of Welham Girls’ School entirely too soppy. Instead, she recommended crisper, tougher fare so we could aspire to admirable, unyielding character traits.

I remember watching the 1962 war film The Longest Day projected on a makeshift screen. Sitting on a wooden bench, we contemplated John Wayne and his indecipherable drawl. To be fair, most of his dialogue was unintelligible due to Mr. Rick's ancient speakers. The noise emanating from the projector competed with the sound of the reels clinking and clanking in the spools. I was Mr. Rick’s chosen assistant, due to my experience at my dad’s movie hall. An unexpected benefit of spooling endless miles of celluloid was getting to choose next week’s film. One summer term, I chose Doctor Zhivago, and Mr. Rick actually managed to get a 16mm print. Seeing David Lean’s film projected onto a set of sewn-together double bedsheets blowing gently in the hot summer breeze did not distract from its impact. The movie fed my incurable romanticism. While I was growing up, popular Indian films, regional cinema, and Hollywood fare were all grist for my early creative mill.

At home, my father always spoke of directors first and actors second, which was bizarre, since nobody I knew paid much attention to filmmakers. It was Dad who introduced me to the great humanitarian filmmaker Satyajit Ray, whose work has never left me. It never crossed anybody's mind that women would want to do anything in movies except act. This regressive, commonplace thinking was everywhere in my life. My uncle, a commander with Air India, was shocked because his fleet had trained a female co-pilot. Women were meant to wear beautiful silk saris, bow their heads, fold their hands in a subservient namaste, and then serve the passengers. They made perfect air stewardesses. The idea of any woman wearing trousers and sharing a cockpit with a captain of an aircraft was unimaginable. Uncle was not a misogynist, but like many men of his generation, he lacked imagination.

The gender roles assigned to us at birth tend to rear their ugly head in the stories and values passed on to us by our families. To break this cycle, it's imperative we teach our children well. When I told my parents I was not going to pursue academics and instead wanted to become a film director, my mom was thrilled. My father, from whom I had imbibed my love of cinema, took his time before he reacted to my career bombshell. Finally, he said, “Remember, your life might as well be dictated by the box office receipts of the opening weekend. Keep in mind that there are two things in life one can never know: when one will die and how a film will be received. As the outcome of both life and film is unpredictable, it's important that you do not compromise on either."

Dad has never spoken about my gender being a handicap. Instead, what concerned him were the unrealistic expectations for anyone starting out in the film business. My struggle has been less about any known anti-female bias in the industry (it's a given), but rather being loyal to one's vision during great times of conflict and upheaval.

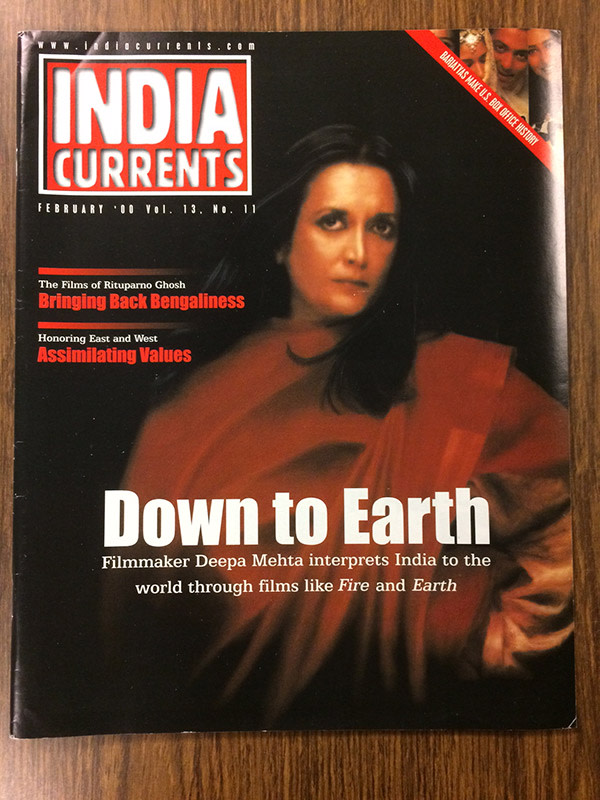

Deepa Mehta graces the cover of India Currents in 2000. Courtesy the Deepa Mehta Archive, TIFF Film Reference Library.

After leaving the University of Delhi, I sold tea at the Tea Board of India in London, England. I was living hand-to-mouth, sharing an apartment with a couple who were convinced they were a reincarnation of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. I started to educate myself by reading anything recommended by my boyfriend at the time, who was attending Oxford. Reading made me think and not go stir-crazy as I sat demurely behind the tea counter in my crisply-ironed sari. Every hour or so, I would look up from a book and say to anyone passing by, “Excellent Darjeeling.”

My Oxford boyfriend and I parted ways. I thought he was a total jerk who quoted Auden far too often, while he thought I had an inordinate imagination (“Too vivid,” he said). Returning to Delhi, I found a job at a small company called Cinema Workshop that made cutting-edge commercials and shorts for the Government of India. Under the supervision of my amazing boss Anil Srivastava, I learned how to record location sound, operate a 16mm camera, and edit on a Steenbeck. I also answered phones and doubled as a gopher on shoots. One day, Anil asked if I was interested in making a two-minute film on how wheat grows. I said “Sure,” although I didn’t have a clue how to do it.

As it turns out, my too-vivid imagination came to my rescue. I started with the image of a farmer smoking a hookah pipe while he sat in his wheat field. The farmer puffs away, looking up the cloudless sky while stuffing tobacco into his pipe, scratching his ear, yawning, staring at his arid field, willing the wheat to grow. Nothing. Eventually, he falls asleep. We cut back to the field. There’s no sign of a seedling, or even a plant. The end. I cut the film with an excellent film editor at the Cinema Workshop. Then I showed it to my boss, who looked slightly bewildered. Thus, the untimely death of my first film, whose story logic (How the hell does one “see wheat grow,” anyway?) only I seem to get.

"To talk about the truth is easy, but to live by it is not." — Bhagavati (Waheeda Rehman), Water, 2005

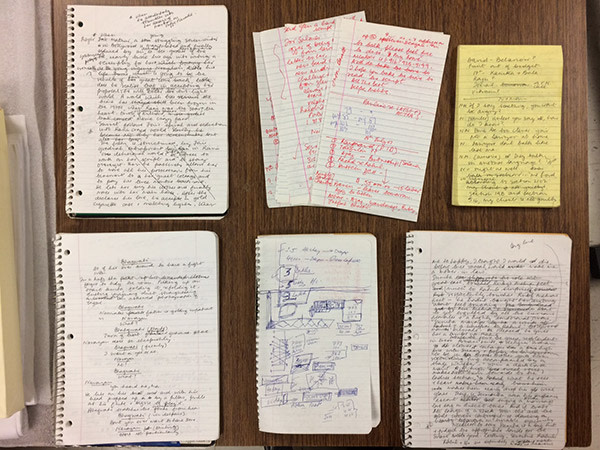

Deepa Mehta's production notes. Courtesy TIFF Film Reference Library.

I made my first feature, Martha, Ruth & Edie, after I had been living in Canada for a few years. At the time, I was totally besotted by Canadian women writers, particularly their short stories. Wouldn't it be terrific, I thought, if we could do a dramatic anthology series for CBC, adapting the short stories of female authors? Especially if they could be written by women, directed by women, and produced by a woman — me. The amazing story editor Barbara O’Kelly and I identified three stories by Alice Munro, Betty Lambert, and Cynthia Flood to produce. Then we hired three female screenwriters (Janet MacLean, Barbara O’Kelly, Anna Sandor) and three female directors (Norma Bailey, Danièle J. Suissa, and myself).

I did the “California Aunts” part of the trilogy with Andrea Martin playing the part of Ruth. I was really nervous: how does one direct actors? Uta Hagen's book Respect for Acting, recommended by Danièle, gave me a glimpse into their headspace. “What do they want?” and “What are they looking for?” became the two questions that stopped me from making an absolute ass of myself. As for the camera, cinematographer Douglas Koch liberated me by saying, "Just tell me what you want to see.” But Martha, Ruth & Edie bombed critically and at the box office. So much for my desire to push female talent forward in Canada. I felt righteously indignant towards critics trashing what I thought was my rather noble endeavour.

The idea for my next film, Sam & Me, came from somewhere deep in the recesses of my subconscious. I was a Canadian who still thought of herself as an Indian. My home was Delhi, yet my daughter was in Toronto, as was my home with my then-husband. It was a confusing period in my life. As an immigrant, why was I still nostalgic for my homeland? How and when does one transfer their allegiance to another country? While I had luckily not experienced any overt racism, I could feel it brimming under the polite Canadian surface.

Therefore, it made perfect sense for me to do a film about Indian immigrants to Canada and their hopes, desires, and tribulations. Ranjit Chowdhry, an extremely innovative young screenwriter and a recent immigrant to Canada (who would also star in the film), wrote the script. It centred around a young immigrant who ends up as a minder to an older Jewish guy (played by Peter Boretski) as they develop an unlikely friendship. We got financing from Wayne Clarkson at the OMDC, and were turned down by Telefilm. With very little money, we started making the film.

Halfway through the shoot, I remember taking too long to respond how I wanted a crucial setup to be executed. Before I knew it, at least five men had jumped in to helpfully take control. One told me (very kindly, he surely thought) I should rest. Then another piped up, saying that I needed a Vitamin B12 shot. You know when your hands get clammy and you can feel the ground slipping away from under you? I can recall feeling just that.

When women on set become self-assured, emphatic, and truly in charge, they are generally labelled “bitchy” — or, even worse, “insecure.” I told everyone on set to take five and had an informal chat with my group of would-be directors. I told them if they ever stepped in the way they had just done, I would laugh outright at them — on set.

Eventually, I decided to come clean and admit to my keys that I knew fuck-all, technically. Guy Dufaux, who’d shot Denys Arcand’s brilliant Jesus of Montreal, came onboard as the DP. His influence has a lot to do with the education I got about lighting, lenses, and, most importantly, mood. Guy taught me to never feel hesitant about expressing what you want to say. As a filmmaker, all you have to do is trust yourself, and if you fuck up, it's no big deal — it's only a movie.

Camilla, 1994.

Sam & Me got to Cannes and won an award. It was a small one, but an award at Cannes nevertheless. What should have been a high point in my career was stunted by going through a rather ugly divorce. So, the highs were cancelled by the lows, which was a great lesson in the unpredictability of life.

Around the same time, I got a call from a guy who said he was George Lucas. He loved Sam & Me and wanted to chat about a series he was doing for ABC called The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones. I replied by saying something like, “Yeah, and I am Princess Leia,” and then hung up on him. When we later reconnected, Mr. Lucas had a good laugh, while I felt like a real idiot.

My next film, Camilla, was offered by Christina Jennings of Shaftesbury Films. It came with a lovely screenplay by Paul Quarrington with Jessica Tandy attached as the star. Camilla was fully financed and the distributor was Miramax. Heady times, indeed. What attracted me to the story was the relationship between the two female leads. I liked that even though one was younger, adventurous, and rather fanciful (played by Bridget Fonda) and the other older, timid, and unsure (played by Jessica Tandy), what they had in common was a love of music. Camilla was a road movie with two luminous actors, and I loved every minute of the shoot. Sadly, it did really badly in Miramax's first test screening, and soon enough, Harvey Weinstein re-cut it and changed the score. I did my director’s cut, walked out, and never saw the film again.

Yet the crash and burn of Camilla turned out not to be the disaster I thought it was. After an appropriate mourning period of about six months, I decided I would make one more film. If that, too, was disastrous, I would get a regular job.

I wrote the screenplay for Fire, my first film in what would be later known as my elements trilogy, based on the idea of women navigating India’s sexual politics and patriarchy. I’d never written a screenplay before, but my friend Barbara O’Kelly said it was easy, claiming: “In Act One, set up your story and characters; in Act Two, it all falls apart; in Act Three, it all comes together. And, oh, throw in a couple of hero scenes — the big, dramatic kind.” Armed with Barbara’s words of wisdom, I wrote Fire and knocked on every door I could to try and find financing. What I got was a big, fat nothing.

Seeing my desperation, my partner (and now husband) David Hamilton stepped in as producer, offering his help in getting the film financed. He had taken a keen interest in the evolution of Fire and had encouraged me to write the script. I was gobsmacked. With the help of Suresh Bhalla, a friend who became an executive producer, they managed to raise enough money privately for us to shoot the film in Delhi. The key crew all deferred their salaries, and David and I were thrilled when after a few international sales, we could actually afford to pay them back. Years later, I found out one of the first investors in the film was actually David. He never got his money back, but to this day, he grins whenever he talks about the toughest deal he put together in his career. David is also my producer to this day. So far, my mother’s warning that people who live together should not work together has come to nil!

Fire, 1996.

We submitted Fire to TIFF, and the Festival did something extraordinary. They decided to open the traditionally Canadian-shot-and-produced “Perspectives Canada” section of the Festival with our film. Cameron Bailey and Piers Handling said that Fire was a Canadian film, as it was written, directed, and produced by Canadians. For us, it was a moment of pure elation.

A few years later, TIFF again did the improbable. They chose to open the Festival with the next film in my elements trilogy, Water. The film’s long journey had been fraught with disaster — the kind where religious fundamentalists threaten your lives and burn down your sets, while proclaiming the film you are about to make is untruthful and hurtful to the cultural sentiments of India. They had also protested Fire, shouting as they decimated movie halls that the film was a misrepresentation of Indian women, as there were no lesbians in India. Go figure that one out.

I experienced a turning point during a plane ride I took from New Delhi to Toronto in 2000. We’d been forced to shut down the production of Water in Varanasi, and I had been in Delhi for an excruciating two weeks, constantly surrounded by the police as I was being hounded by trolls who’d characterized me in the press as the evil woman who had sold her soul to the West by living up to the worst stereotyping of India. I remember sitting on the plane, exhausted. As it took off, a feeling of such relief washed over me that I very uncharacteristically burst into tears. I felt for the first time ever I was going home to Canada, a place that I could equate with safety. Becoming Canadian, of course, means I can be whatever I want. The reboot of Water years later and its subsequent screening as the opening film of TIFF was another landmark in my career. A few months later, the film would be nominated at the 2007 Academy Awards in the “Best Foreign Film” category.

Hollywood, Bollywood, and all the other “Woods” around the world are still being run by boys’ clubs. The good news is, slowly but surely, a dent is being made in the barriers that protect this hallowed ground. While not all powerful men are intimidated by strong women, many still are. It's partly about the unknown factor — the idea that women are now your competition. I think these men need to loosen up, because the more variety we have in our creative voices, the better our films will be.

Throughout the years, I’ve heard lots of ridiculous things, but what irks me most is equating a diversity quota with a gender one. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard this excuse: "Oh, we already hired a non-white guy. On our next round, we’ll hire a woman.”

I love TIFF and am eternally grateful for them not only showcasing my work, but also positioning me as a Canadian filmmaker. I admire what TIFF stands for, especially now that it has made a mandate to advocate for women in film with the Share Her Journey campaign. We all need champions while we try to get our work seen and our voices heard. Let’s be honest: it is a battle.

For me, the female gaze is a given. I am a woman and the way I look at relationships, men, and stories is unique — it simply has to be. As I grow older, my concerns are changing, as well as the political and gender-based investigations in my work. Stories move me and are notorious for taking us on the paths we know little about. I empathize with any female filmmaker who has a story she wants to tell, and would implore them to tell the industry to go fly a conceptual kite. It is so important for the women starting out in their filmmaking careers not to cater to what they think the market wants. Make the films and tell the stories that move you — the stories you’re so desperate to tell that you will die if you don't. As my dad rather cryptically suggested many moons ago, we never know when we will die, and we will never know how a film will fare. So why compromise on either? Live life on your own terms. Make films on your own terms too.

TIFF wants to support and empower female voices. Donate today to our Share Her Journey campaign.

TIFF has made a five-year commitment to increasing participation, skills, and opportunities for women behind and in front of the camera. We will prioritize gender parity with a focus on mentorship, skills development, media literacy, and activity for young people. Donate today to help TIFF support and empower female voices like our campaign ambassador Deepa Mehta.

React to The Review

We believe a powerful film or work of art — or, uh, email newsletter — should generate a reaction. That's why we're thrilled when readers of this humble publication choose to reach out and tell us what they thought. If you've got something to say, please SEND US A LETTER and SUBSCRIBE HERE.

Below is a letter from our last issue, curated by Canadian writer, producer, and actor Sarah Kolasky.

__RE: ISSUE 50 The Future Is Female __

Good article written by the emerging female director, in her 30's! Good luck to you ladies. — From a feminist who is 71, Mariana G.