The Review/ Digital Digest/

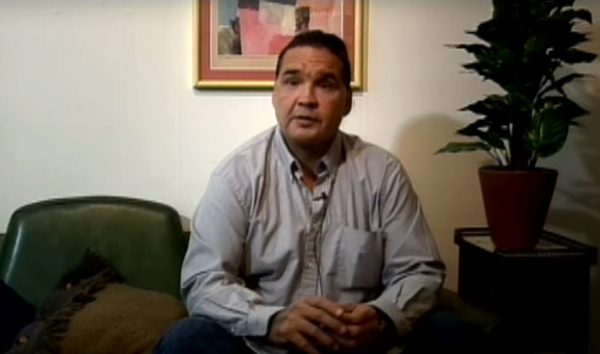

How an Iranian master influenced a Canadian filmmaker: Hugh Gibson curates The Review

Abbas Kiarostami's surprising effect on a TIFF '16 doc

*"It is good fortune that... only human nature provides us with a refuge that has any depth to it.”* - Abbas Kiarostami

Hugh Gibson

Documentarian. Social justice advocate. Kiarostami fan.

[@midlampfilms](https://twitter.com/midlampfilms) [@thestairsdoc](https://twitter.com/thestairsdoc)

See his fim The Stairs, on now at TIFF Bell Lightbox

When Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami passed away in July, I was devastated. For me, he was among the world’s greatest artists: endlessly brilliant across multiple disciplines (among them cinema, photography, writing) and highly inspirational. Seeing Kiarostami in person was a major event, first at the TIFF Cinematheque in 2001 (presenting ABC Africa), then during an "In Conversation With" at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in November 2015.

When I learned of his passing, I was completing my first feature as director, The Stairs, which screens at TIFF '16. I couldn’t help but reflect on what Kiarostami’s work means to me and his influence on my career.

I find it difficult to express the depth of my feeling around Kiarostami's work. I think he might even be pleased by that. His films are filled with scenarios that capture quiet moments of contemplation, or which pose questions that aren't necessarily made explicit or answered. He frequently invites the viewer to fill in the blanks themselves. In Jonathan Rosenbaum and Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa’s book, Abbas Kiarostami, the director is quoted: "My intention… is to show signs of reality that viewers won’t necessarily comprehend but will nonetheless feel."

That reminds me of the experience of viewing some of my favourite paintings, especially Mark Rothko’s. While Rothko was a purely abstract painter and Kiarostami’s photographs and films often depicted landscapes and poetic realism, they both specialized in simple expressions of complex ideas. Rothko expressed his feelings about humanity, philosophy and existence by painting giant colour fields. Viewing them up close in a gallery can be deeply emotional, in a way that goes beyond words. I find Kiarostami’s work similarly transcendent.

Kiarostami was also a minimalist who strove for a distillation of form. In his notes on the premiere of Ten, Kiarostami recalls a story about an old man who, late in life, could only utter two words: "It’s strange!" He marvelled at how the man's very experience of life had been distilled down to two words, wondering if "that’s the story behind minimalism too." He closes by writing, "This film is my own 'two words.' It sums up almost everything. I say 'almost' because I’m already thinking about my next film. A one-word film perhaps."

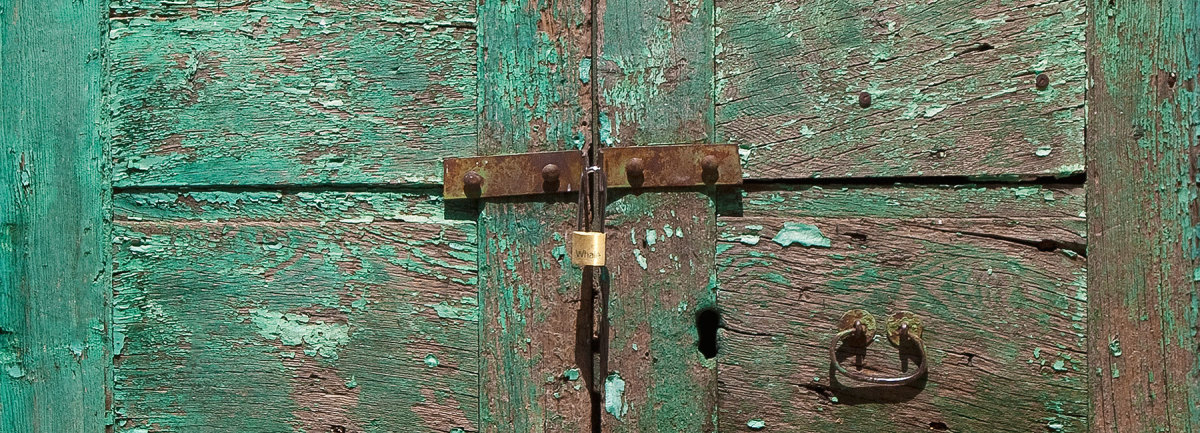

At his recent exhibition at the Aga Khan Museum, titled Doors Without Keys, Kiarostami created images of various doors where viewers would invent backstories for each image. The same can be said of the iconography in his films — a winding road, a lone tree in a field. These images tend to be deceptively simple and rich with possible interpretations. Every film allows for a very personal experience, and repeated viewings inevitably reveal something new.

In 2011, I began directing my film The Stairs, a documentary (playing at TIFF this year) that follows three people in Toronto's Regent Park who survived decades of street involvement and now work in public health to help their community.

I had originally been hired to make some educational videos for some local non-profits. When the experience turned into something very personal — both for the remarkable people I met and for myself — I was compelled to go further, uninhibited. The film’s characters have experienced poverty their whole lives, using drugs and working in the sex trade. Over the five years I spent filming and talking with them, they struggled with their tenuous lifestyles and past choices, while also showing the human side of their world that we don't often see. Each of my subjects is funny, articulate and surprising: mother, grandfather, poet; each has great concern for their community's safety.

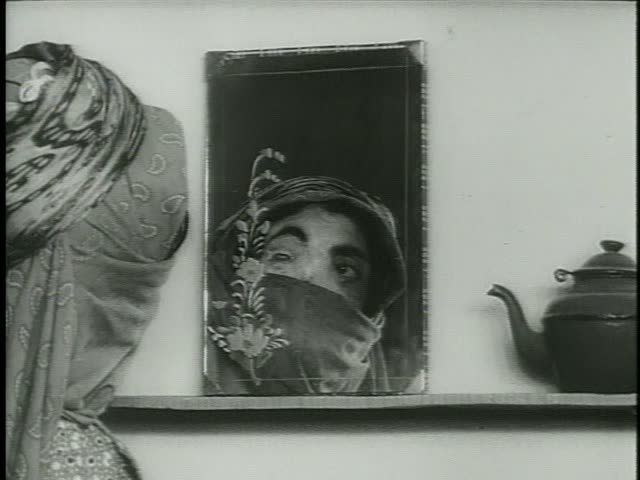

While preparing for The Stairs, I revisited some of Kiarostami's films, in particular Close-Up, And Life Goes On and Taste of Cherry. The subject of his films and style are very different from mine. But I wanted capture the humanity of marginalized people and understand their experience. Kiarostami's films contain a humanism that I find uniquely affecting. And on the subject of Iranian cinema, which has a rich humanist tradition, some great examples are Forugh Farrokhad's The House is Black, and the films of Jafar Panahi (Kiarostami's former protégé).

My preparation involved looking at other films for reference, including Pedro Costa's In Vanda's Room (a masterful opus about drug users in Portugal, also set in a troubled neighbourhood undergoing massive change), and Alan Zweig's A Hard Name, which is the most intimate documentary I've ever seen about poverty. Zweig’s startlingly honest examination of ex-cons, connected by experiences with childhood sexual trauma, is raw and minimalist: like its characters, the film is laid bare. I liked how his subjects were presented respectfully, without pretence or judgment. To my great fortune, Alan was my executive producer for The Stairs.

Preparation is very important – but when you actually go to shoot, the best-laid plans sometimes go out the window. I often had to film very quickly, improvising and working spontaneously. It was an approach that suited this film, which is focused on the characters' voices and personalities. Since they tend to live moment-to-moment, shooting this way over the course of five years led to many unplanned occurrences. Notable among them was that scenes kept happening in cars, which is a staple of Kiarostami's films.

In 10 on Ten, Kiarostami describes why the car is his favourite location: it's an intimate environment where two people can talk comfortably, which creates the perfect setting for dialogue. Characters can look where they want, they feel security. Everything is in place for spontaneity, since there’s no room for crew or equipment.

I wasn't consciously aware of any of this at the time. I filmed in a car for many reasons, but it was always appropriate for the scene. (Plus, traveling and transience are important to the story).

There ended up being numerous important scenes in cars: in one, Roxanne takes us to her former corner late at night and recounts her experiences as a sex worker. She's lit only by the overhead car light, and it feels very intimate. She felt comfortable, as though we were on her turf, resulting in a wonderfully candid interview.

Another important scene involves Greg, who I’d begun to follow in 2011, but who disappeared for quite some time due to homelessness and other events that are described in the film. When we had finally reconnected, we only had a short period together. It began to rain. An impromptu interview in my car was a suitable makeshift option. It also provided a secure environment, which Greg lacked at that point in his life (living in shelters, or outside). It led to Greg opening up, and it's one of the strongest moments in the film. Of course it wasn't until much later that I realized I’d unconsciously drawn on Kiarostami’s influence.

I did make one conscious reference to one of my favourite filmmakers. While filming one of the last scenes, I noticed a framed photograph of a solitary tree, just as you’d see in many of Kiarostami's photos or films. I placed the photo in the background, in the corner of the image: a subtle nod, which I was previously intending to keep to myself. Now that he's gone, I'm glad it's there as a tiny reminder of his legacy and how his work inspired me.